‘Personal obsession’: Bong Joon Ho details creative process in master class

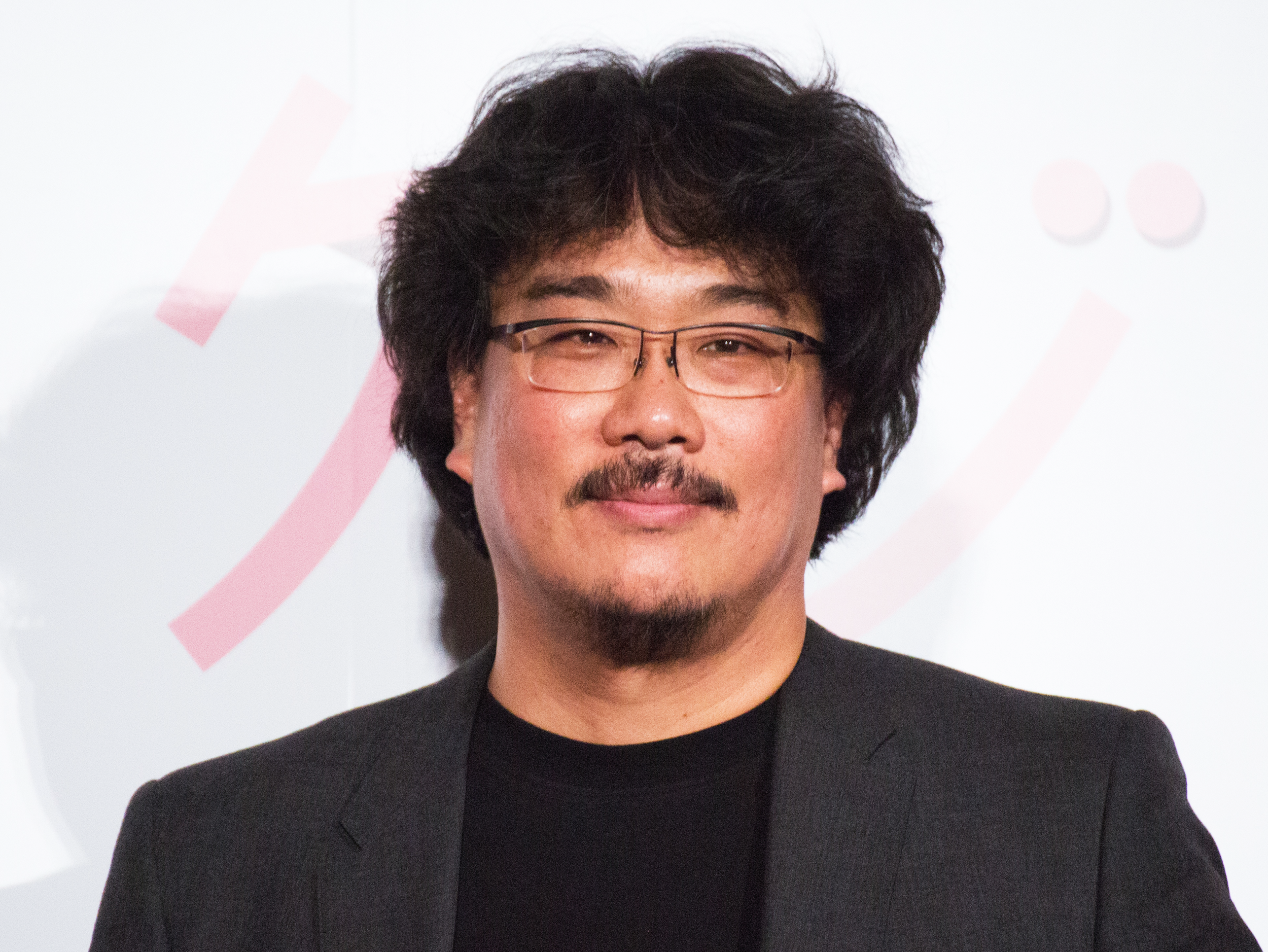

Academy Award-winning director Bong Joon Ho spoke to Chapman students in an April 7 master class moderated by Nam Lee, a Chapman film studies professor with shared South Korean roots. WikiCommons

Ten years ago, Chapman students in the Randall Dining Commons ate breakfast with a bespectacled, small-budget Korean film director. They had no idea, at the time, that the man sitting in their cafeteria would go on to win an Academy Award for Best Director.

In 2011, Bong Joon Ho was invited by Chapman film studies professor Nam Lee to speak as the keynote guest for an iteration of the Busan West Film Festival on campus. The acclaimed filmmaker slept for two nights in Chapman dorms, allocating any time that wasn’t spent hosting panels or attending screenings to sitting down with students in the cafeteria for meals.

“He had this kind of generosity about him, and he spoke really well,” Lee said, describing her first impression of Bong to The Panther. “I could feel his openness and generosity. He was really kind to people, really kind to our students and willing to talk.”

A decade later, Bong returned to Chapman to speak with students in the Dodge College of Film and Media Arts for an April 7 master class Lee moderated. Bong announced at the event that he is currently in the process of working on two projects at once, one in Korean and one in English. He is unsure which will reach production first, but revealed he finished the Korean script in January and has visual concepts ready for both films.

Storyboarding is a critical aspect of Bong’s creative process, he said. That habit began from a childhood dream of becoming a comic book artist in addition to a filmmaker. He typically has creative authority of the writing and development of his films, which Lee attributed to a major difference between Korean and American filmmaking; Korean directors have more control over their work than any other member of the crew.

“When you’re writing a screenplay as a director, you already have most of the image and sound in your head,” Bong said. “In terms of how I conceive of the idea, it’s different for every film. But the commonality in all of those is just a personal obsession. To make a film is a very long, complicated and grueling process, and my personal obsession is what allows me to endure that whole process.”

“When you’re writing a screenplay as a director, you already have most of the image and sound in your head. In terms of how I conceive of the idea, it’s different for every film. But the commonality in all of those is just a personal obsession. To make a film is a very long, complicated and grueling process, and my personal obsession is what allows me to endure that whole process.”

Lee, in addition to moderating the master class, also has a personal relationship with Bong and has extensively researched the director’s full filmography.

Born and raised in Seoul, South Korea, Lee traveled to America in 2000 to pursue master’s and doctorate degrees in critical studies in film at the University of Southern California. Lee, at the time, had 15 years of experience under her belt of entertainment reporting on some of South Korea’s top filmmakers. But it wasn’t until six years after her journey, at a reception for the American Film Institute festival, that she would first establish connection with Bong.

“I met him for the first time there to say ‘hello’ and introduce myself,” Lee told The Panther. “The second time (I met him), ‘Mother’ was released in Los Angeles and the distribution company had a reception and invited him. I went and said ‘hello’ again, and that was about three years apart, but somehow he remembered me.”

Although virtual, Bong’s appearance April 7 was no less popular than his first visit to Chapman. Shortly after a brief introduction, the Zoom call reached its maximum user capacity of 1,000 participants — the most of any master class hosted by Dodge College this semester — forcing any lingering students to remain in the waiting room until a spot opened up from another user leaving. The event was originally intended to be divided into a 30-minute interview moderated by Lee and 30 minutes of participant questions, but Bong stayed 20 minutes over schedule to finish talking with students.

To help translate the conversation between Korean and English, Bong shared the spotlight of a Zoom camera with 25-year-old Korean American filmmaker Sharon Choi, who went viral on the internet for her close working relationship with Bong at the 2020 Academy Awards. Choi recently finished her own feature script, which is in the process of development.

“I read it; it’s quite good,” Bong said April 7, gesturing to Choi as she laughed bashfully, adjusting the position of her glasses.

The director’s 2019 feature film “Parasite” broke barriers. It became the first foreign-language film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, spreading awareness of the rise in commercial success of Korean cinema. Bong also received Oscars for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay for the film.

Prior to the success of “Parasite,” Lee noted that Korean films were not always welcomed in the international sphere, based on the jarring and often unfortunate realities of South Korean life.

“Korean stories do not unfold in a way that American stories unfold, and I think it has to do with the historical experience,” Lee said. “Hollywood movies are about an individual hero … He or she or they have a goal — something that they want to achieve — but then there is conflict and difficulty. Whatever the difficulty is, the Hollywood film is saying that if you try hard enough, you can overcome it and everything will be OK at the end. But in South Korea and in many other post-colonial societies, history tells you that there are some things that you can never resolve.”

The breadth of Bong’s filmography provides an outlook into some of the lived experiences of South Koreans, while also providing a critique of social issues. For example, “Parasite” grapples with class disparity, while 2017’s “Okja” delves into the corruption of the meat industry.

Chapman professor Nam Lee (left) invited film director Bong Joon Ho (right) as part of the Dodge College of Film and Media Arts' iteration of the Busan West Film Festival in 2011. Photo courtesy of Lee

Lee comments on this social criticism, the altruistic meanings and the visual aesthetics within Bong’s work in her September 2020 book “The Films of Bong Joon Ho.” She kept in touch with Bong throughout the writing process, saying he made time to speak with her every time she visited South Korea.

Lee’s interest in the director traced back to his 2003 release of “Memories of Murder,” which unveils the harsh military dictatorship of South Korea in the 1980s as an expositional vehicle for a true crime murder mystery.

“What was very impressive about his approach was that it is a failed story. The detectives fail to catch the killer,” Lee told The Panther. “He was advised by many industry insiders that he had to change the ending, because a failed detective story is a commercial suicide; the people would not want to watch a movie that ends in failure. But he kind of kept his own thoughts, and he didn’t focus on the killer and the crime. He made it into a story about 1980s South Korea under a very harsh military dictatorship, and it was more about (that).”

That same dictatorship, both Bong and Lee agreed, was responsible for a complete lack of access to creative content under the oppressive hand of censorship. As a child, Bong would obsessively search through the newspaper to find the programming schedule for each day to watch whatever new film he could find.

“These (films) were all broadcast on the public TV network, and they were heavily censored because the administration was very conservative,” Bong said April 7. “I watched all these films as the heavily edited versions. It was only later on when I was able to access these films again through Blu-ray and these retrospectives that I realized I had missed a bunch of scenes when I first watched them.”

Now, Bong consciously works to provide an unadulterated portraiture of the inherent trials and tribulations of contemporary life — a visual platform for stimulating socio-political conversation. The release dates of his next two films are not yet determined.

The Panther will release a follow-up profile on Bong in early May following a scheduled email interview. In the meantime, Leatherby Libraries announced the addition of Lee’s book into their collection, giving students the opportunity to read more about her interpretations of Bong’s work.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly indicated Bong Joon Ho had lunch in the Randall Dining Commons instead of breakfast. This information has been corrected.

Clarification: Nam Lee studied critical studies in film at the University of Southern California.