Review | Escaping 2020’s Wasteland

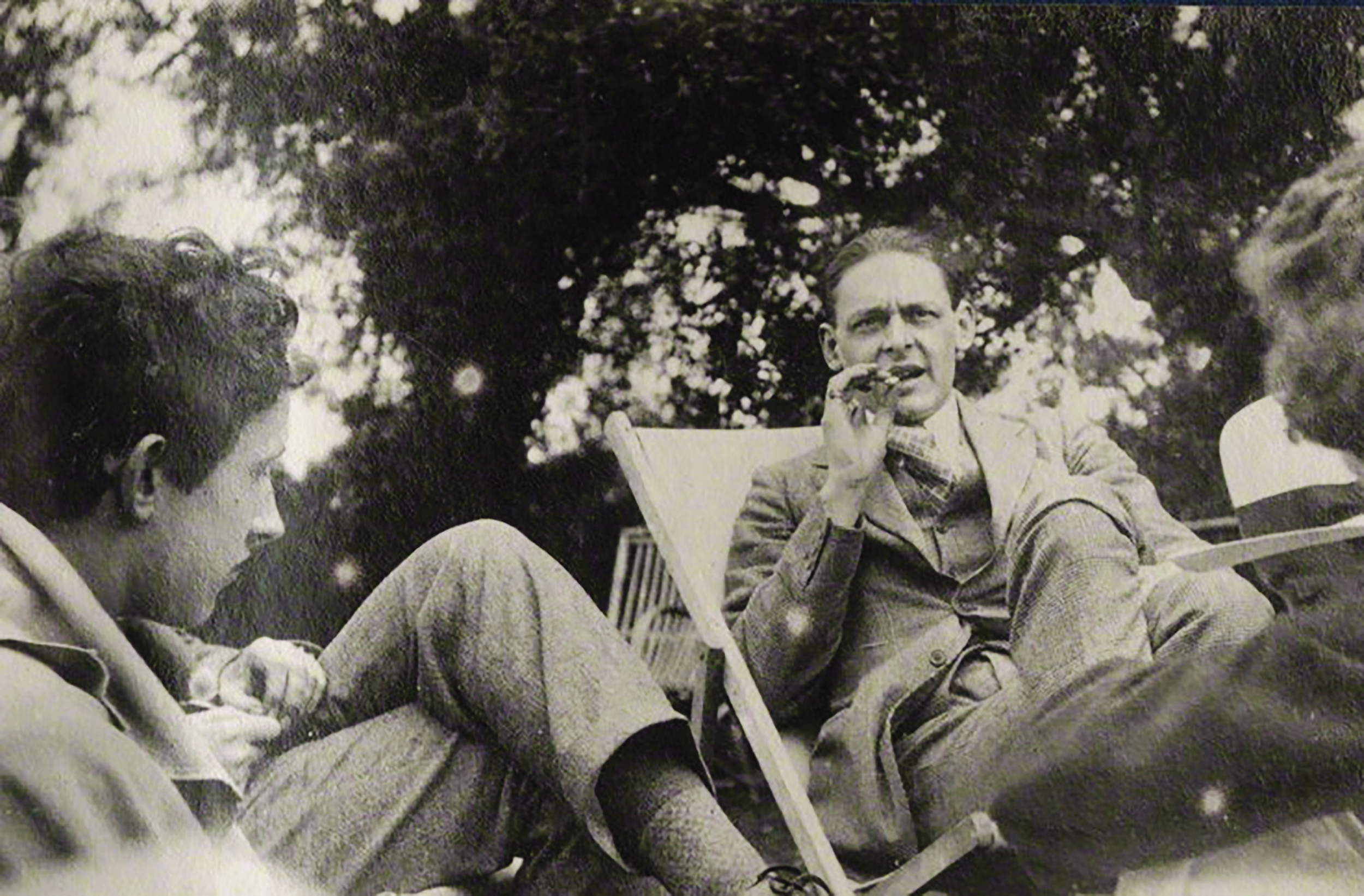

T.S. Elliot’s 98-year-old poem “The Waste Land” can revive our collective humanity. Review written by Caden McQueen, sophomore film studies major. WikiCommons

Amidst the doldrums of quarantine, I felt as if time had lost all meaning. Days turned into weeks turned into months as the monotony of being cooped up inside melted together into a grayish slurry of tedium, loneliness and worry that plagued my every waking moment.

The all-consuming thought of how we could possibly come back from the onslaught of tragedy and injustice that seemed to pour out of every corner of the Earth tormented me. Being unable to do anything more than spread awareness and donate what I could while living in a household with immunocompromised family members made it all the more torturous.

Racked with all these emotions, I – like many others – tried to turn away from the proverbial hellfire that raged outside my bedroom window and distract myself with whatever escape I could get my hands on.

Video games, music, film, television, social media – I immersed myself in anything I could to briefly stave off reality, constructing a comfortable shelter of screens that I could retreat into whenever I felt like. While bathed in their sickly blue light, the world outside became no longer an object to me.

Why pay any mind to the suffering outside my bedroom window when these tens of thousands of pixels stood eager, requiring nothing more from me than the swipe of a finger or the press of a button to meet my every passing fancy?

Despite the nagging voice in the back of my head telling me I was burning time or I could be doing more, I continued to resign to their cold embrace day after day – not because I was apathetic, but because it was easy.

One morning, the endless content stream I had set up for myself fed me a 24-minute YouTube video of actor Alec Guinness reading T.S. Elliot’s “The Waste Land” – a notoriously complex poem that I’d always heard about, but never had the courage nor the drive to read.

At first, I found Elliot’s bizarre blend of German and English prose largely esoteric and confusing. But upon hearing the second stanza, I was snapped out of my stupor. Guinness’ words that were moments ago so honeyed and vague suddenly rung out like gunshots in my ears.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Elliot was right; in his time, just like ours, capitalistic society had become, as he said, “a heap of broken images” – the only difference between 1922 and today being the sheer saturation of them. It dawned on me that these devices I had spent so much time preoccupied with could never capture life as faithfully as one’s own eye.

The films, albums, video games and otherwise were only deeply flawed depictions of the human experience that stemmed from their various authors’ imperfect perceptions of truth, bearing nowhere near as much fruit as witnessing something for oneself – “fear in a handful of dust,” as Elliot put it.

Immediately, the purpose of Elliot’s inclusion of dreamy accounts of childhood memories that struck me as so abstruse upon my first listen became apparent. These moments, although largely meaningless to me, were meaningful to him.

That is not to say that in this poem Elliot deftly labels all artistic endeavors as post-structuralist hogwash and declares that only he can create valuable art, nor that I am claiming something similar; clearly, I have found much meaning in Elliot’s work and through my assessment of his own “broken image,” I too am creating yet another to throw atop the heap.

But through this image, Elliot is attempting to teach how to reinvigorate fulfillment not only in oneself, but in the world as a whole through a great reconvening with the most raw and emotional elements of humanity.

In the poem’s second to last stanza Elliot offers three Sanskrit words: “datta” meaning generosity, “dayadhvam” meaning empathy, and “damyata” meaning control.

Only through controlling your own selfish consumption and desire can you find the power to give back and feel with others. Only through a combination of all three of these ideas can the synthetic apathy and lackadaisical indifference that our modern world fosters be defeated.

Do not let that blue light overtake you as it did me. I know it’s easy to seal yourself off in this time of isolation, but you must resist the urge to delve headlong into the endless flow of distractions that constantly surround us, and maintain your connection to humanity. Only then can we all escape the “waste land.”