EXCLUSIVE: 7 things to know about Chapman’s agreement with the Charles Koch Foundation

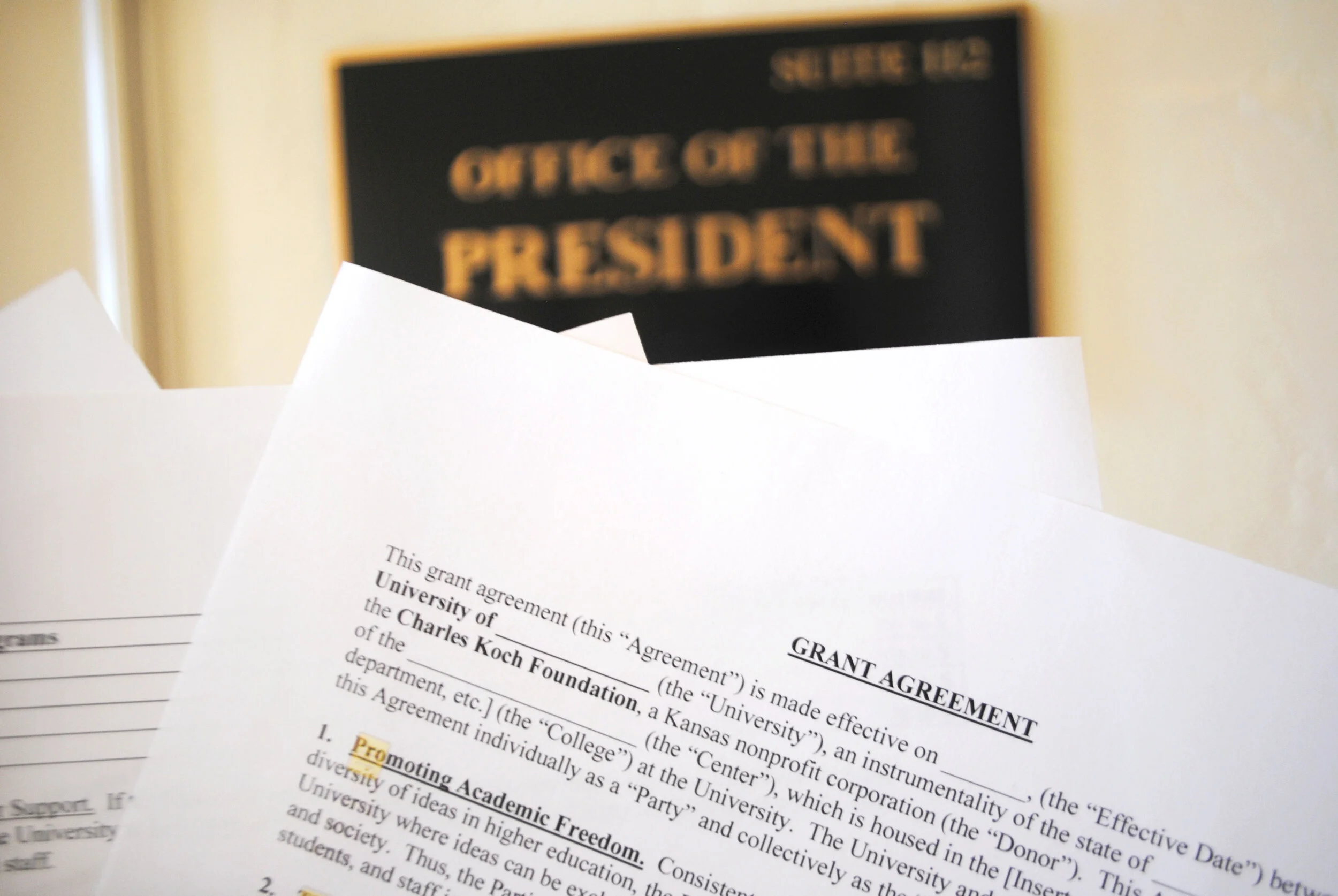

The Panther viewed the donor agreement between Chapman and the Charles Koch Foundation – which has donated millions to the university – in a May 8 meeting with President Daniele Struppa and David Pincus, the faculty senate president. The documents above are part of a sample agreement that the foundation has on its website. Photo illustration by Bonnie Cash

The Panther sat down May 8 with President Daniele Struppa and David Pincus, the faculty senate president, to view the donor agreement between Chapman and the Charles Koch Foundation. The next day, Ralph Wilson, co-founder of the UnKoch My Campus campaign, told The Panther that this is the most progress he’s seen at a private university.

Less than two weeks after George Mason University’s president opened an inquiry into the Koch Foundation’s funding April 27, saying that it fell “short of standards of academic independence,” the foundation agreed to the meeting at Chapman, though the terms stipulated that The Panther could not take pictures, write notes or directly quote the document.

In December 2016, Chapman received a $5 million donation from the Charles Koch Foundation to help establish the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy, which aims to combine the studies of humanities and economics. Some Chapman professors have questioned the transparency and integrity of the donations at Chapman, as, before May 8, administrators had only shown excerpts of the agreement during faculty presentations.

Wilson, who has spent years combing through donor agreements between universities and the Charles Koch Foundation, said that “all the normal strings seem to be attached” in Chapman’s donor agreement.

Here are seven takeaways from Chapman’s agreement with the foundation.

1. The Charles Koch Foundation can withdraw its funding, giving as little as 30 days’ notice, if the mission behind the funding is not being met. The institute’s mission is to “challenge the perceived tension between economics and the humanities” and combine research and education “in the spirit of Vernon Smith,” a Nobel laureate who was key in securing funding from the foundation, according to the institute’s website and proposal, which The Panther reviewed in the donor agreement.

But Struppa said that, in his time working with the foundation at George Mason and Chapman, the foundation has never pulled funding, or even attempted to.

Wilson called the foundation’s ability to withdraw funding “absolutely critical,” as it allows the foundation to pull its donation at any time during the agreement.

2. The agreement between the foundation and Chapman spans 10 years. This means that, after the five years of funding are up, Chapman must continue funding the institute and its faculty on its own if the foundation chooses not to donate more money.

That 10-year agreement “says a lot” about Chapman’s commitment, Wilson said, as the type of positions funded by these donations are often long term.

“(The donation) is the school giving away tenure-track lines to a private donor,” he said. “These positions, as they’re created, exceed the five- or even 10-year parameters here. It means that they are creating this center with the intention of having a very long-term impact on campus.”

“The donation is the school giving away tenure-track lines to a private donor.”

3. Chapman receives the funding every year after the foundation reviews a yearly report from the university detailing the Smith Institute’s progress. Although the report that The Panther viewed included information about faculty research, new hires and courses, it is up to the director of the institute to decide what’s included in each annual report.

Chapman gave its second annual report to the foundation this week, Struppa said. The Panther also reviewed guidelines from another Chapman donor, the National Science Foundation, which requires similar reports for its multiyear grants, too.

Struppa told The Panther that, compared to Chapman’s annual budget of about $400 million, what the Charles Koch Foundation contributes to the university isn’t significant.

“We would not compromise who we are for $1 million a year,” he said at the meeting.

4. If Bart Wilson, the institute’s director, steps down or is fired, the foundation must be notified, but it has no say in who is hired as the new director. The hiring process would follow the university’s standard procedures.

Ralph Wilson said that this requirement is an example of the foundation’s “monitoring.”

“(The donation) is not a gift from the university to do what they want. It’s funding for a trusted free market scholar to do what the donor wants,” Ralph Wilson said. “If any piece of that changes, they need to be on the alert, because that paranoid element of control is called in and triggered at that point.”

“We would not compromise who we are for $1 million a year.”

5. The validity of the donor agreement was contingent upon two other anonymous donors signing the agreement. These donors contributed $10 million total, which, coupled with the Charles Koch Foundation’s $5 million gift, established the Smith Institute. Provost Glenn Pfeiffer told The Panther in November that these other donors wanted to remain anonymous because they didn’t want to get “caught up and have people accusing them of things and being associated with this.”

6. Chapman can’t disclose that an agreement between the foundation and the university exists without written permission from the foundation. “I’m not sure why, to be honest,” Struppa said, when asked why that portion of the document exists. “Every private foundation would do the same.”

7. The foundation must review and approve any university-generated publicity before its release, something that Struppa said is “absolutely standard,” though a sample agreement from the foundation doesn’t mention publicity approval – just review.

This story is part of The Panther’s continued reporting on the Charles Koch Foundation and its donations to Chapman. To read past coverage, click here.