Chapman takes a legal look at how to handle immigration policy after removal of Title 42

Following the lift of Title 42, immigrants now have new rules in applying for asylum. Chapman law faculty presented a webinar on Sept. 20 explaining the situation and what this means for immigrants’ legal rights. Photo courtesy of Unsplash

Now that Title 42 has been dismissed, the United States southern border is facing a massive amount of migrants seeking asylum to live in America.

Title 42 was first introduced by the Trump Administration as a public health order that would deny migrants access to asylum, therefore expediting the process of sending them back to Mexico or their home country. This policy was carried on through Biden’s administration and was enacted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic as a means of preventing the virus from entering the U.S.

But now, with the global health emergency being formally deemed over by the World Health Organization, Title 42 is lifted — leaving a post-COVID-19 United States with the question: What now?

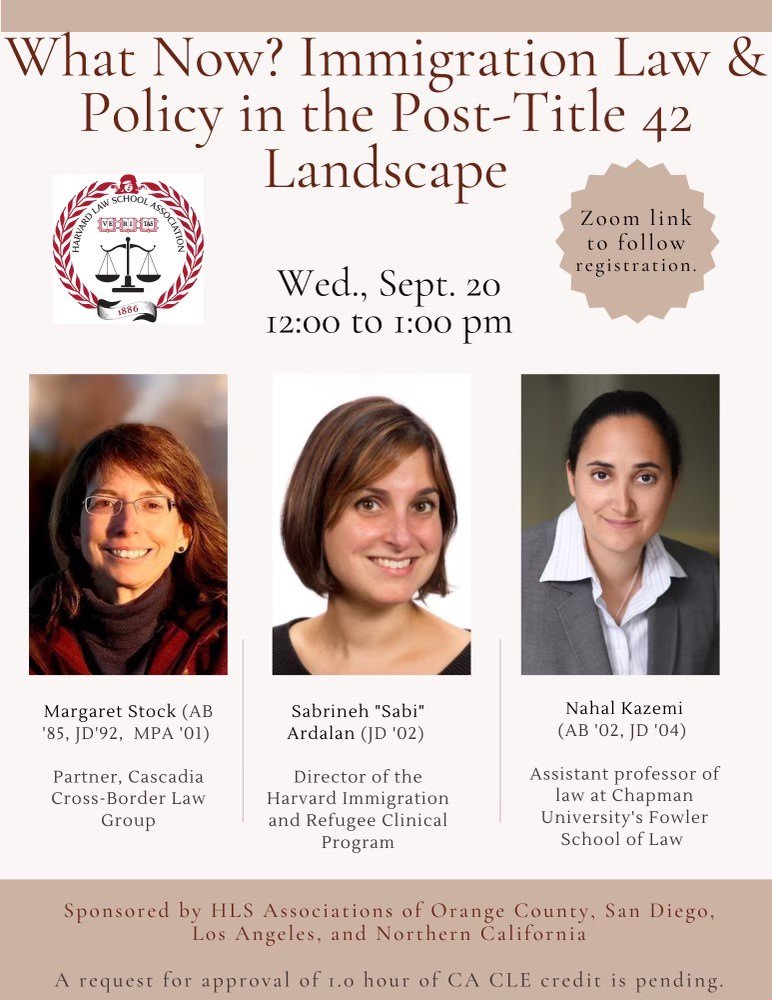

A webinar presented on Sept. 20 by Chapman University assistant law professor Nahal Kazemi, with guests Margaret Stock of Cascadia Cross-Border Law Group and Sabi Ardalan of Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, sought to explain the situation and answer that essential question.

U.S. law provides migrants with the right to apply for asylum, which protects those who are attempting to flee their home country due to fear of persecution. Refugees who are granted asylum are allowed to live and work in the United States, but as Kazemi points out, this isn’t as effective as it sounds.

“One of the biggest issues facing asylum applicants is that they cannot obtain a work permit for the first 180 days after filing their claims,” Kazemi told The Panther. “This means most are reliant on family, friends or charity to support them for the first six months after they apply, which can be a major strain on communities.”

“One of the biggest issues facing asylum applicants is that they cannot obtain a work permit for the first 180 days after filing their claims. This means most are reliant on family, friends or charity to support them for the first six months after they apply, which can be a major strain on communities.”

Now, with the Title 42 restrictions lifted and asylum applications being accepted again, the southern states have seen a large influx of migrants attempting to cross the border and seek refuge in America. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has responded by sending these migrants in buses to blue cities including Los Angeles and New York.

The webinar, hosted by assistant law professor Nahal Kazemi, featured guests from Cascadia Cross-Border Law Group and Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program. Flyer courtesy of Harvard Law School Association

“The situation at the southern border right now is a big mess, and that’s a polite way to put it,” Stock said during the webinar.

To better control the immigration system at the border, the Biden Administration has implemented Title 8 immigration protocols. With this, legal migrants will be allowed to plead their case through a credible fear interview. This interview has the individual claim their fear of persecution, and it will be determined if they fit the need for asylum. If their reasons to enter the U.S. are deemed valid, then they can remain in the country and make their case in court.

However, since there’s nearly three years worth of migrants waiting in Mexico to enter America, the new policies also make it difficult for those who do not follow all the rules.

“The new post Title 42 rules are being challenged in federal court,” Kazemi told The Panther. “Regardless of whether they remain in place, there is a massive backlog in processing asylum claims in the United States, and it often takes years for cases to be resolved.”

Migrants who failed to receive authorization to cross, as well as those who did not schedule an interview with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, are subject to expedited removal. Also, those who try to enter illegally will be deported and may face persecution and a five-year entry ban.

“Under Title 42, it was exceedingly difficult for anyone to obtain asylum in the United States because of the policy of immediate expulsion,” Kazemi explained in an interview. “Now, migrants can use the CBP One app to make an appointment and seek asylum, so in that sense, it is easier.”

“Under Title 42, it was exceedingly difficult for anyone to obtain asylum in the United States because of the policy of immediate expulsion. Now, migrants can use the CBP One app to make an appointment and seek asylum, so in that sense, it is easier.”

While those who are able to access the CBP One app and make an appointment have an easier process, those who cannot access the app or who are not aware of it are still facing challenges. And though migrants are no longer facing mass expedited removal, there are still challenges in accessibility for individuals seeking asylum.

“Migrants have a credible fear interview (CFI) typically within 24 hours of being detained,” Kazemi said. “It is very difficult for migrants in these circumstances to obtain legal assistance in preparing for their CFI.”

Stock also spoke in the webinar about how difficult it is for migrants to successfully seek legal counsel to help them through the process.

“There’s pretty much no involvement of lawyers because it’s almost impossible for lawyers to get involved in this process,” Stock said during the webinar. “It’s happening so fast, and there’s no easy way for a lawyer to get involved. “In fact, the system seems designed to cut the lawyers out of it.”

Stock continued: “Just having that knowledge base and having a lawyer explain all that to you before you walk up to the border is really helpful to a lot of people.”

For students who are interested in further research on the subject of immigration policy, Kazemi recommends visiting Human Rights First, American Immigration Council and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.