Students advocate for removal of controversial film poster from Dodge College

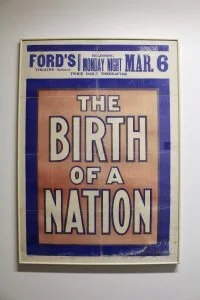

““‘The Birth of a Nation’ is a racist film, it is a racist poster, it is hate speech. There is absolutely no way around it,” said Arri Caviness, a first-year graduate student, who posted a photo of her and other students by the poster on Twitter. Dodge College tweeted back, but some students believe that the controversial poster is not being taken seriously. Photo by Cassidy Keola

It’s easy to spot the collection of film posters and artwork hanging on the walls of Chapman’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. The artwork, donated by renowned filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille’s estate, includes the original posters promoting D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent epic drama, “The Birth of a Nation,” a controversial film that many believeinspired the Ku Klux Klan revival in Stone Mountain, Georgia.

Arri Caviness, a first-year film production graduate student, decided to draw attention to the poster.

On March 29, Caviness tweeted a photo of herselfand five others next to the poster with the caption “Why does Dodge College, @THR’s (The Hollywood Reporter) 6th best US film school, still condone the celebration of white supremacy?”

It took the school five days to respond on Twitter.

“‘The Birth of a Nation’ is a racist film, it is a racist poster, it is hate speech. There is absolutely no way around it,” Caviness told The Panther. “This poster is a daily reminder of the casual, violent racism that was commonplace in the early 1900s and remains commonplace to this day.”

The movie, which is historical fiction, depicts the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the relationship of two families during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. The film has been widely criticized for what many say is a glorification of the Confederacy, but some in the film industry continue to praise it for its innovations.

The film was “astounding in its time” and furthered filmmaking technique, according to “The Parade’s Gone By…” a book by film historian Kevin Brownlow. It was the first time that “dramatic close-ups, tracking shots, and other expressive camera movements” were introduced.

“These so-called merits do not erase the simple fact that this film is undeniably racist,” Caviness said. “A film that dehumanizes black people, celebrates lynching and is, in no small part, responsible for the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, is not worthy of our praise.”

On April 2, an account associated with Dodge College tweeted back saying, “We hear you. We are currently having discussions with senior staff about these posters.”

Phumi Morare, a film production major and one of the students in the posted picture, responded to Dodge’s tweet that same day.

Morare’s tweet thanked Dodge College for its response and said that students had already talked to Dodge staff.

“We understand these discussions have been happening for years without any action,” she wrote, before asking for more a more concrete response.

Although the Dodge College Twitter account responded to Caviness’s original tweet, some students aren’t sure how seriously the poster’s presence is being taken.

“Actions speak louder than words and I hope it’s not swept under the rug,” said Danielle Gibson, a film production major who was also in the picture with Caviness. “To me, it’s like seeing a Confederate flag or a statue of a Confederate figure. Its presence is intimidating.”

Bob Bassett, dean of Dodge College, declined to provide a statement to The Panther unless it was published in full.

In a phone interview, President Daniele Struppa said that while he has not seen the film, its induction into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry means it’s “not just any movie.”

“It would seem strange that as a university, we would obfuscate that,” Struppa said, adding that he believes censorship in any form is bad, even when done with the best intentions. “That’s not the way we learn. Instead of erasing, we remember and we criticize and discuss and educate.”

Struppa wants to hold a student-led discussion about why the movie is problematic, he said, and what can be learned from it, “rather than taking down the poster as if it never existed.”

Caviness’ post has been retweeted by 31 people, including Oscar-winning writer Charlie Wachtel, the cowriter and coproducer of the 2018 film “BlacKkKlansman.”

Wachtel and his “BlacKkKlansman” cowriter, David Rabinowitz, attended a screening of the film at Dodge March 7.

“I’ll admit it was a little uncomfortable seeing this poster on campus the same day we did a Q&A for blackkklansman (sic),” Wachtel wrote in his retweet.

In the Q&A that followed the screening, Caviness asked what the writers thought about “The Birth of a Nation” and how universities should address the legacy of the film. Rabinowitz responded that he thinks “it’s a pretty good thing” if “BlacKkKlansman” helps remove similar films from a pedestal.

“There are a lot of well-edited films that aren’t ‘The Birth of a Nation,’” Rabinowitz said.

Richard Brody, a film writer for The New Yorker, wrote that the worst thing about “The Birth of a Nation” is “how good it is,” though its pro-Confederacy sentiments are “grossly apparent.”

“I understand that they have it up because of its significance in film history, but it’s put up without context to how ridiculous and racist it is,” Gibson said. “It would make more sense in a museum or in a textbook, or at the very least, with a disclaimer about it.”

Caviness and Gibson are part of a group of students who have been coordinating efforts to have the poster removed. They have had discussions with Dodge faculty members and are drafting an open letter to Bassett.

“Our goal isn’t to erase the film from history, but the film should be acknowledged for what it is because of how blatantly awful it is toward people of color,” Gibson said.

The burden to advocate for the poster’s removal should not fall on black students alone, Gibson said.

“To ignore its blatant hatred is to condone the idea of white supremacy in media. I believe Dodge is better than that, and hopefully they can prove that to me,” she said.