Opinion | Poetry retains relevance, intimacy in modern day

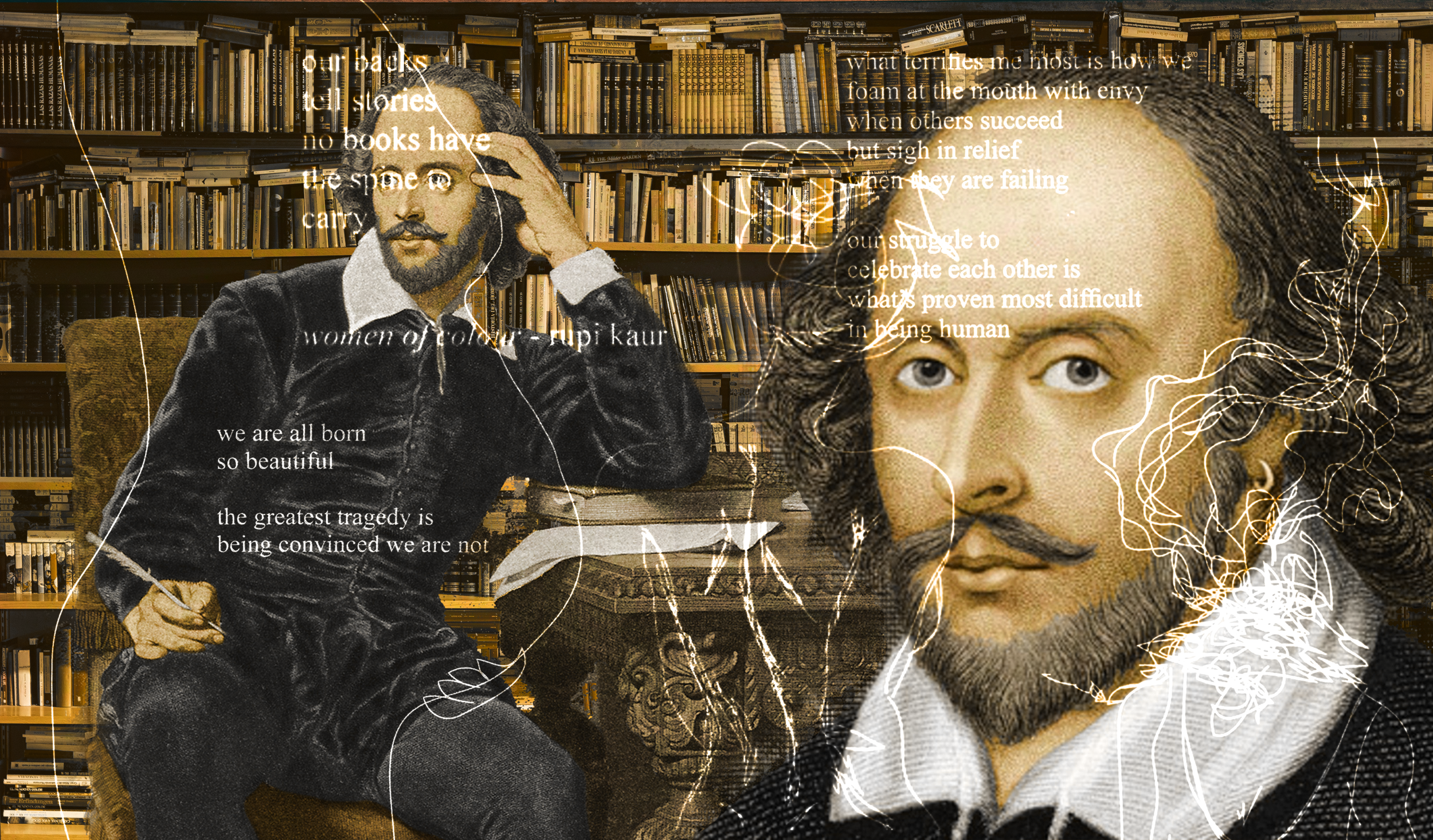

Poetry remains an intimate mode of storytelling in modern day that, by nature, is inherently queer. Photo illustration courtesy of Sam Andrus

When I turned 16, I felt like the leash my parents had kept fastened tightly around me had finally been cut. Blissfully unaware of the reality that I had simply never ventured far enough to feel it go taut, I began to frequently sneak out of my childhood home.

When the sun set, I often found myself slinking off to perhaps the last place one would expect to find a person my age: a poetry circle.

In the quiet tea room where the circle took place, you could order decaf tea on creaky tables for one, or (if you squeezed) two, because poetry is not something that attracts those who have someone or something better to do in the middle of the night.

Molly Stepvac, junior English major

The circles happened at midnight and on the weekends, because poetry is also not something you can leave your day job for, and it was all very romantic.

I loved the veteran who’d never gone to war but made us sit up straighter and yearn for something to die for when he spoke, the woman who fluttered on stage and introduced us to her fairies and talking lilies, the old man who mused about his younger self spending hot and lusty nights with other young men in a country that wanted him dead.

There was an unspoken intimacy among us; as we shared our poetry, it was as if everyone’s little life was cut into pieces and carefully passed around the room. These pieces were often sharp, their jagged edges whetted with emotional turmoil, but we clutched onto them regardless for each other’s sake.

Everyone was tired in some way, and everyone was angry. And yet, we all took solace in these moments that we shared together.

Moments like these are everywhere. But unless you look for them, you’ll miss them altogether.

Poetry is supposed to be cryptic. Unlike writers of other ilks, the poet often exists in total obscurity, their work known only to themselves and perhaps a few other local beatniks. Beneath the shrouds of metaphor and idiosyncratic word play, they are free to express themselves however they’d like.

The medium thus affords a great deal of secrecy, and often attracts those who have secrets they want to make into something worth sharing. As a result, poetry is inherently — and functionally — queer.

Growing up as queer kid, there’s something magnetic about poetry that drew me in. Shel Silverstein’s poem “The Romance” tells of an elephant and a pelican who marry because their names don’t rhyme — “as good a reason as any for two to wed.”

It’s a love poem without gender, about as far removed as possible from the sanctimonious, rigidly defined perceptions of marriage that have dominated our culture for so long. Silverstein’s delightfully silly style resonates if only because of his commitment to allot dignity to his characters and take them seriously.

The animals marry, they eat lemons and limes, they are happy.

It’s this kind of abstraction from reality that makes poetry resonate so deeply with closeted queer kids. You read something and, for the first time, get to think, “That’s just like me!”

The “how” and “why” are completely irrelevant in that private moment of connection; the sense of feeling seen by words that you can hold in your tiny hands overwhelms, and the world begins to feel a little less lonely.

Richard Siken comes to mind as a modern poet who broke into the mainstream of recognition with his 2004 book “Crush,” an unequivocally, unabashedly gay collection of poems both tender and erotic.

Similarly, Christopher Soto’s poetry grapples with trauma and identity, growing pains and all the anger, sadness and love that knowing about the world brings.

Eileen Myles, acclaimed for her experimental style and contributions to dyke literature, is yet another brilliant contemporary poet. Their art is not contextualized by their queerness; their queerness is the context itself, and it is the life force of the genre.

There is no shortage of bad poetry out there. There are scores of books thrown together for quick cash where free form becomes a complete abandonment of form at all, and where you can almost see the editor erasing all traces of what might have once been an author. The result is a poem just vague enough to entice teenagers to slap a few all-lowercase lines to their Instagram stories.

Good poetry is equally as abundant, but you will have to look for it. And I urge you to look.

Attend a poetry reading if you can. The Ugly Mug in The Orange Circle hosts one every Wednesday at 8 p.m. Poetry is beyond the haikus we learned in high school and broader than Edgar Allen Poe’s raven-clad shoulders. It is about connection.

To me, some of the greatest poets of our generation are the ones I met in that tea room all those years ago, whose names I don’t know but whose life-splinters I carry with me as they carry mine. Go out and find your own great poets.